There is many an idea presented as new that has its roots in days long past. We too often forget that the way things are done now was not always so. We too often presume that the ways of today are destined to remain.

Jackie McCartin – Beautiful Reflections

Today we are reinventing the old idea that we can make landscapes – farms and forests – yield many things of use to man and nature alike. That doesn’t just mean looking at a forest or a field as more than a producer of wood fibre or grass and grain; it also means the development of a finer textured landscape where neither forests nor field dominate. Forests of old were as much about food as they were about wood, and landscapes in older countries than ours reflect the potential of small sites rather than the singular obsessions of a narrow profession. For those who see landscapes, the focus shifts from a resolution of 100 ha pixels to fractions of a hectare. You find the potential in the finer resolutions.

In New Zealand we paint our land with a very broad brush – especially in the hill country. Our legal boundaries reflect not so much the history and potential of land – trees best suited here, crops there, pastures yonder – as the tedious chore of some bored surveyor biting off 1000 acre quadrangles. And within those borders we have tended to focus on one thing or another – a sea of ryegrass or a sea of radiata pine. Anything else is treated as incidental to the primary purpose. So mushroom collecting or deer stalking, for example, are only tolerated so long as they do not compromise the machine that produces the ‘main crop’.

The last decade has seen both foresters and farmers rethink the idea that we concentrate on one thing over a broad swath of land. The Perriams of Bendigo Station in Central Otago have turned a rabbit infested run into a mixed landscape of grapes, gold mining history and tourism, wild food, low-micron wool, quality wine, and recreational sport – and we mustn’t forget Shrek. The Perriams produce pheasant, rabbit and other game for the tourists to eat accompanied by local wines. They create experiences far richer than just the taste of a thing, and by so doing create value. That is a far cry from a degraded sheep run. The Perriams now have a problem. They don’t have enough rabbits, and are harvesting the neighbours. So they turn problems into profits, and poorer areas of land into opportunities.

Ernslaw One is doing a similar thing in their forests. They have interests in forest food; in ginseng and edible fungus, and – now – freshwater crayfish, koura. Koura indicate clean  water, and so demand high environmental standards. They therefore represent a delicacy that is more than just a tasty meal; they represent a clean landscape, one that people will pay for. That is also an *experience*. This is not a commodity that is forced to take an ever smaller price; the nature of the experience gives the product a premium, and the seller the market position to pick and choose who has the privilege to dine out on the story.

water, and so demand high environmental standards. They therefore represent a delicacy that is more than just a tasty meal; they represent a clean landscape, one that people will pay for. That is also an *experience*. This is not a commodity that is forced to take an ever smaller price; the nature of the experience gives the product a premium, and the seller the market position to pick and choose who has the privilege to dine out on the story.

Roydon Downs south of Te Puke is an example of a landscape that combine field, forest, game birds, recreation, wetlands, complementary cashflow, low risk and beauty in one piece of land. That is a way of doing business from the land that is the opposite of our usual style.

But such thinking is still not the mainstream. Farmers and foresters too often forget that they are land managers first, and farmers and foresters a distant second. History does not give them the luxury of presuming that the future will remain a static and predictable path. It will surprise. It will change. And anyone thinking within the box that says there ought to be one and only one thing in some spurious pursuit of a temporary efficiency – radiata pine or ryegrass – will likely get buried in it; the box that is.

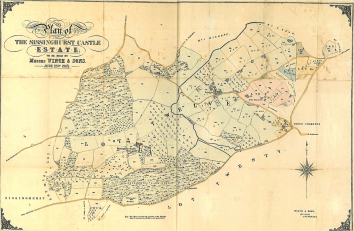

History does more than indicate a pattern of change through time. It also demonstrates the potential for change and variety in space. If you look at ordinance maps of the rural landscapes of southern England you realise how young is New Zealand. The Weald of Kent, home of Churchill’s beloved Chartwell and estates like Sissinghurst, are famous – and scenic – because of the patterned landscape of fields and forests.

The arrangement of those patterns is seldom some rich man’s exercise in creating a canvas to please the eye of some Romantic poet. These are in the main functional landscapes, reflecting history, particular land quality, and the dependence of rural communities on both food from the fields and the goods and services provided by the woods. No community could survive in the pre-oil age without a forest. They provided so much of what is now imported or produced from far away sources of oil and aluminium. And it could never be a simple forest; it had to be complex to provide all the values demanded – from pig fattening acorns to barrel staves, firewood and herbs.

Rather than creating what they presume to be efficiencies and more profit, that obsession with the one thing has often resulted in the loss of money and opportunity. That is because the pursuit of cost efficiency presumes that nothing will change other than the cost. They do not see what might change to their detriment because specialists don’t like to think that hard. Alongside that obsession with specialisation rides the production of low value commodity, whose prices spiral downwards while we hope for the miracle that will turn that trend around, while doing absolutely nothing about it. Meanwhile, there are high value goods and services neglected or completely ignored because the blinkers of convention don’t allow us to whisper their names.

We don’t think of other things, so waste money forcing land, rather than working with it. For example, we continually develop and redevelop bits of land that is always going to be a cost to keep in grass, and many seldom think whether it is all worth it to every decade spend ten thousand to return seven thousand, before we spend the next ten again. At the opposite end of the scale, we plant radiata pine on hay paddocks, and seldom think twice. We make uniform and homogeneous what would be more profitable and enjoyable as a mixed and patterned arena.

Ernslaw One and Bendigo Station are but two examples of another way, one that we will see more of as the years go by and the more simple-minded men in suits realise that their specialised sophistication is also the reason why history will show them up as naïve and lacking judgment. They have focus without breadth, and that is the worst of combinations.

Landscapes achieve a greater richness when they are viewed with a broad eye that senses both history and the potential to bring things together to make a delicious cake. It’s a hell of a lot nicer than just producing the single ingredients like flour. For truly edible landscapes, the magic is in the mix.

Chris Perley

Thoughtscapes

Brilliant. Some wonderfully inspired language and analogies in here, Chris. Thank you. Am forwarding it aroundâ¦..keep cooking/ bakingâ¦

Appreciatively,

Phyllis

Phyllis Tichinin

General Manager

0800 878 343 or 06 874 7897

Fax 07 888 4869

PO Box 8055

Havelock North, 4157 NZ

info@truehealth.co.nz

.

Reblogged this on Chris Perley's Blog.

Thank you! Forest gardening is my love and I am constantly amazed by the ecology of the experience. Diversification for me is learning from our past and forests are a key thing missing today.

Great article. Thanks Chris.